By the AZFPI Board

Part I – Utility-Scale Solar in Yavapai County

This is the first article in a two-part series about proposed utility-scale solar and battery storage farms in Yavapai County

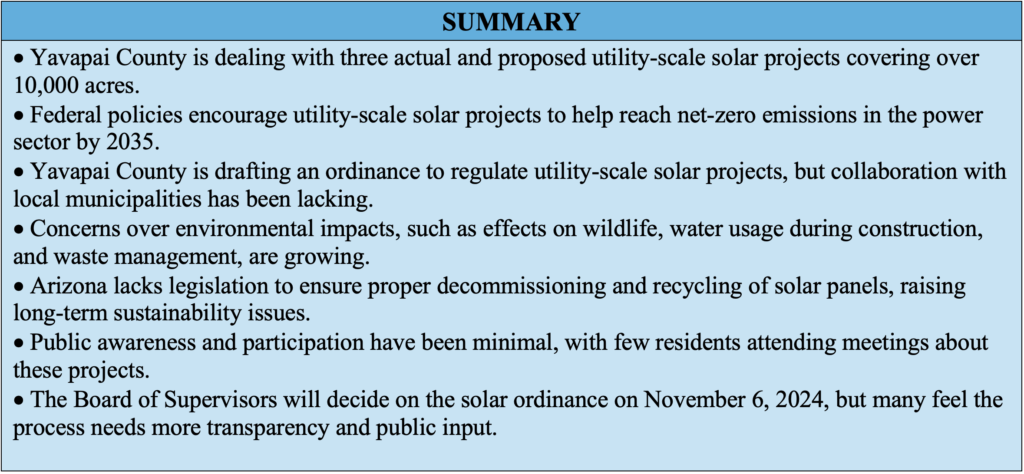

Remember playing “Whisper Down the Lane” in school as a kid? The game usually starts with the teacher, who whispers a sentence into a student’s ear. That child instantly whispers whatever he thinks he hears to the classmate behind him. By the time the last child repeats aloud whatever he hears, it bears absolutely no resemblance to the teacher’s original sentence. So of course this is met with howls of laughter. Regrettably, this game is now being played out in real-time in Yavapai County when it comes to an already approved utility-scale solar facility1 and two proposed projects together encompassing over 10,000 acres.2 To date, only a few residents have been included in this latest game of Whisper Down the Lane. And no one is laughing while Yavapai County attempts to wrap its arms around the impacts of this unprecedented and novel land use.

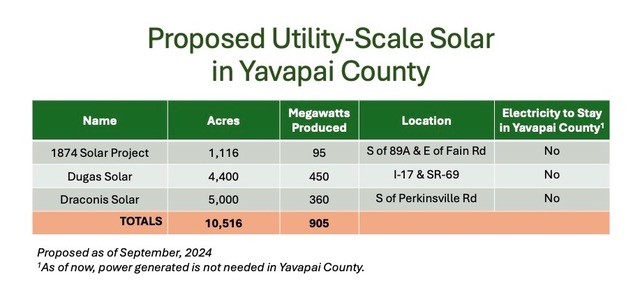

Three actual and proposed solar projects have been in the works for years, and the public is just now receiving fragments of information. First, there is the 95-MW (megawatt) 1874 solar project approved by the Yavapai County Board of Supervisors on January 6, 2021. This 1,116-acre site is located south of Highway 89A and east of Fain Road.

Next, there is the proposed 450-MW Dugas utility-scale solar project to be located on 4,400 acres of Arizona State Trust Land in the area of I-17, north of SR-69 (two miles from Arcosanti). On November 11, 2023, Candela Renewables secured a 30-year lease with the Arizona State Land Department. Yet as early as September, 2021 ⎯ over two years before the State Land lease auction ⎯ Candela met with select groups in Yavapai County to tout the benefits of this project. Recently, Candela withdrew from the project and Longroad Energy plans to assume the lease and finance the project. At this time, the project is still in the planning stage, and no formal proposal has been submitted to the Yavapai County Board of Supervisors.

Finally, there is the 360-MW Draconis Interconnection utility-scale solar project financed by Lightsource (British Petroleum – BP) to be located on 5,000 acres south of Perkinsville Road within the town of Chino Valley and in unincorporated Yavapai County. This project also includes 5½ miles of 500-kilovolt transmission lines connecting to APS’s existing Yavapai substation in the Prescott National Forest. Leaflets left in residents’ mailboxes by BP advertised a public meeting in August. This was the only notification residents, county supervisors, and the Chino Town Council received. At this time, no formal project proposal has been submitted to the Chino Town Council or the Board of Supervisors.

Why Utility-Scale Solar Facilities?

One of the goals of U.S. federal energy policy, in an attempt to reduce reliance on fossil fuels, is to achieve a net-zero power sector by 2035.3 As a way to achieve this worthy goal, federal policy encourages the growth of renewable energy sources such as wind, solar, and geothermal power. Early on, federal and state tax incentives accelerated the solar energy industry’s efforts to bring, photovoltaic (PV) roof-top solar to residential and commercial users by offering a solar energy tax credit for installation of PV panels on rooftops.

But now federal tax and land use incentives are rapidly encouraging efforts to bring large, utility-scale, industrial solar facilities online as quickly as possible. Long-time environmental advocate, the Sierra Club, states that it is necessary to “act quickly and decisively to reduce carbon emissions through a revolution in energy systems.” The Sierra Club, along with the federal government, support and encourage utility-scale renewables (wind and solar) on public lands and disturbed/degraded private land.4 According to their website, the Sierra Club also believes there is a need to find a balance between renewable energy development to avoid the worst impacts of climate change, while still protecting natural ecosystems and treasured landscapes.

And herein lies the problem facing Yavapai County and much of the western United States where sunshine is abundant.5 The speed at which the federal government and its private sector partners are moving to build thousands of acres of utility-scale solar projects is not keeping pace with the necessity for a wide-range assessment of the environmental and social costs of these facilities. This means that regulations aimed at minimizing the impacts on native plant and wildlife species, heat island effects, water use during construction, location issues, fire danger, waste management, and decommissioning are minimal or non-existent. For example, only the state of Washington has legislation requiring solar manufacturers to finance the recovery and recycling of panels sold within the state; it’s the most advanced legislation focusing on PV panel recycling so far.6 Last year Arizona’s governor vetoed legislation requiring owners of utility-scale solar projects, to not only have a decommissioning plan in place, but also to post a bond (essentially insurance) to cover costs if their solar company goes bankrupt or they otherwise try to walk away.7

Yavapai County’s response to the over 10,000 acres of three pending solar projects has been to draft an amendment to its zoning ordinance to regulate utility-scale solar projects. This effort only came about because of a request from Supervisor Harry Oberg (District I) in October of 2023. The draft ordinance attempts to inject some regulatory boundaries for utility-scale solar projects ⎯ at least in the county. However, at this point, none of the county’s municipalities are working on similar ordinances, although Chino Valley is closely watching the county’s efforts. Further, county development services staff publicly acknowledged they did not work with any of the county’s municipalities when drafting their ordinance. In contrast, county staff did acknowledge negotiating key ordinance provisions with industry types such as the Arizona Solar Energy Industries Association (AriSEIA)8 and APS, as well as select conservation groups. County staff’s failure to consult surrounding municipalities is notably lacking. If there was ever a need for regional cooperation ⎯ this is it.

County Development Services staff initially presented the ordinance to the Board of Supervisors on June 19, 2024. This was followed by two Planning and Zoning Commission meetings and two additional Board of Supervisor meetings. Attendance at these meetings was sparse, which begs the question: How is it a public meeting if the public didn’t attend? It wasn’t until the last county meeting on September 4, 2024 that a fair number of citizens attended and commented on this ordinance. This was likely due in no small part to a Prescott Daily Courier article on August 19, 2019 which depicted Chino Valley residents and leadership as “surprised” by a proposed “large solar project” (Draconis) located primarily in Chino Valley with portions extending into the county.9

Although the September 4 public hearing covered the county’s proposed ordinance ⎯ and not the Draconis project ⎯ residents’ comments reflected concerns about impacts from a large project such as the 5,000-acre Draconis proposal. Of the 40 written public comments received before the September 4 meeting, 23 were opposed to the ordinance as written and wanted stronger restrictions, 7 were neutral and 10 were in favor of the ordinance as written.10 Additionally, the majority of in-person speakers on the day of the public hearing favored an ordinance with stronger restrictions to protect residential neighborhoods, recreational areas, water, and wildlife from the environmental and social costs noted above.

The Board of Supervisors is scheduled to consider the utility-scale solar ordinance for adoption at its November 6, 2024 meeting. The urgency of climate change cannot be denied. And asking hard questions about large utility-scale projects does not make one “anti-solar.” But this, and other solutions to our climate crisis, must include a clear-eyed view of impacts and unintended consequences. Rushing to craft an ordinance without engaging the region’s municipalities and with only minimal public notice and input is not an effective approach.

The September 4, 2024 Board of Supervisor’s meeting showed the “solar whisper” begun years ago, is now a “shout,” and no one is laughing. The latest draft of the proposed ordinance is nowhere on the county’s website for the public to view (an older version is available).11 The minutes from the September 4, 2024 public hearing on the ordinance with requested changes are similarly unavailable. Yavapai County needs to do a better job of informing the public and soliciting input on one of the most significant zoning issues in decades. A good start would include holding a series of public meetings around the county dedicated solely to the discussion of utility-scale solar, as well as facilitating a regional dialog with municipalities. Yavapai County leadership must exercise their duty to manage the delicate balance between the role a utility-scale solar project plays in the transition to renewable energy, versus the potential lasting negative effects on our region’s ecosystem.

Part II of this article will focus on the environmental and social costs of utility-scale solar ⎯ costs which must be addressed and mitigated to the extent possible by the ordinances to be drafted by Yavapai County and each municipality within the county.

Note: Yavapai County Supervisor Mary Mallory contacted us and said the County did reach out to the following municipalities when drafting this ordinance: Sedona, Cottonwood, Jerome, Clarkdale, Wickenburg, Prescott, Prescott Valley and Chino Valley. Only Chino Valley responded and County Development Services held two meetings with them.

REFERENCES

1Ground-based, utility-scale solar panel installations used for electricity generation of 1-MW or greater are commonly referred to as “solar farms.” (March 2024). www.nrcs.usda.gov

2This figure includes the already operational 235-acre APS utility-scale solar facility in Chino Valley.

4Sierra Club website. https://www.sierraclub.org/climate-and-energy

5Solar is Booming (article). https://insideclimatenews.org/news/26062023/solar-water-desert-center-california/#:~:text=Even%20if%20it%20wasn’t,20%2C000%20acre%2Dfeet%20a%20year

6 https://www.dsireinsight.com/blog/2023/10/27/the-state-of-solar-decommissioning-policy-then-and-now; Researchers in other nations such as Thailand, Bangladesh, and Malaysia, have urged their governments to adopt hard-line policies to force the manufacturers of solar PV materials to consider the consequence of their products on the environment and manage solar panels’ end-of-life as hazardous waste. An overview of solar photovoltaic panels’ end-of-life material recycling. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211467X19301245

7 https://insideclimatenews.org/news/25012024/inside-clean-energy-decommissioning-solar-plants/

8Arizona Solar Industries Association is as the name suggests, an industry advocate. https://www.ariseia.org/

9Prescott Daily Courier. https://www.dcourier.com/news/draconis-energy-proposes-huge-energy-project-letter-to-community-reveals/article_a63852f6-5e38-11ef-973d-1fcbae025e51.html

10Yavapai County Board of Supervisors September 4, 2024 Agenda and associated documents. https://destinyhosted.com/agenda_publish.cfm?id=92827&mt=ALL&vl=true&get_month=9&get_year=2024&dsp=ag&seq=1934

11Yavpai County’s Draft Utility-Scale Solar Ordinance available at the time of this writing. https://www.yavapaiaz.gov/files/sharedassets/public/v/1/meetings/pz/second-draft-zoa-sec-501-and-sec-608-solar-facilities-ordinance-revised-7-28-24.pdf